MI SELECCIÓN DE NOTICIAS

Noticias personalizadas, de acuerdo a sus temas de interés

The guerrillas lost on the battlefield. But they rack up victories in politicized courts.

When Secretary of State Mike Pompeo extradited Andrés Felipe Arias to Colombia last year, it signaled a lack of U.S. interest in human rights and democratic norms in that country. With an order last week to put former Colombian President Álvaro Uribe under house arrest, Colombia’s Supreme Court has sent a signal back: Message received.

Mr. Uribe and his former agriculture secretary, Mr. Arias, were both U.S. friends. While fighting extradition Mr. Arias testified in U.S. court in Miami that the U.S. Embassy in Bogotá had recognized him as a Colombian political target when it helped him flee to Florida in 2014.

That turned out to be obvious when, in the face of scant evidence, Colombia’s Supreme Court gave Mr. Arias a 17-year sentence and an US$8 million fine with no opportunity for appeal. As I wrote in November 2018, even “murderers in Colombia don’t get 17 years.”

Mr. Pompeo shipped Mr. Arias back anyway, to satisfy a demand from the Colombian Supreme Court, which is highly politicized and also has great influence over extradition to the U.S. Now the high court has detained Mr. Uribe. He will remain under house arrest while it investigates allegations of witness tampering and procedural fraud and decides if he should be tried.

Mr. Uribe’s political party, Centro Democrático, released a document last week alleging that in 2012 left-wing senator Iván Cepeda had been fishing for false witnesses against Mr. Uribe in Colombian jails, and abroad, to frame him as a paramilitary collaborator.

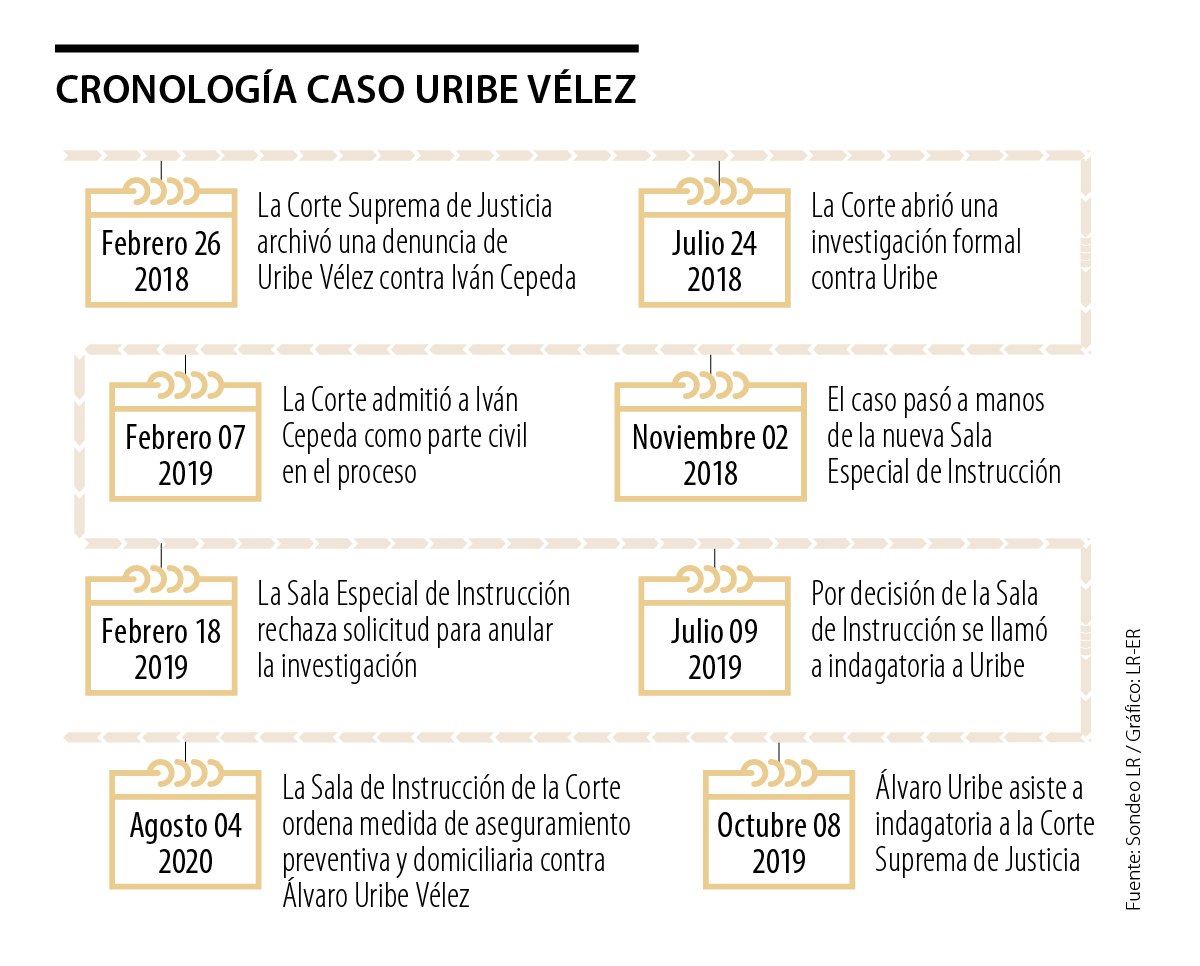

The document further states that Mr. Uribe filed complaints with the Supreme Court in 2012 and 2013 about that alleged witness tampering by Mr. Cepeda but the court refused to investigate. Instead, according to the document, in February 2018 the court made Mr. Uribe the subject of an investigation-without informing him. A week after that investigation began, Mr. Cepeda’s lawyer filed a complaint with the court against the former president for manipulation of witnesses. Five months later Mr. Uribe was notified by the court that he was being investigated for witness tampering.

The Colombian left is crowing about how Mr. Uribe’s house arrest shows that no one in the country is above the law. That’s risible coming on the heels of the 2016 “peace” agreement, forged in Havana, that gave unqualified amnesty and seats in Congress to Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc) terrorists.

In a national referendum, Colombians rejected that deal. But then-President Juan Manuel Santos ignored the vote. Plenty of criminals in Colombia are indeed above the law.

The narcotrafficking guerrillas were supposed to go straight but the U.S Drug Enforcement Administration, working with Colombian law enforcement, alleged that it caught Farc bigwig Jesús Santrich in a cocaine deal in 2017. The U.S. wanted him extradited, but the Colombian Supreme Court freed him. He promptly fled to Venezuela.

So let’s drop the phony-baloney about equality under the law. The Uribe case reeks of score-settling. He is a conservative politician who turned the battlefield tide on the Farc both as a governor and later as Colombia’s president. He’s now a sitting senator and putting him under arrest is political, as was the jailing of his protégé, Mr. Arias.

When I first interviewed Mr. Uribe in 1997, he was a popular governor of the department of Antioquia, where he backed legal civilian intelligence networks that assisted the army in battling the guerrillas and paramilitary. During his tenure, the northern region of Urubá was largely pacified by the military.

Shortly before Mr. Uribe’s August 2002 inauguration as president, a group of U.S. legislators-including Democrats Jan Schakowsky of Illinois, James McGovern of Massachusetts and Bernie Sanders of Vermont, who have a history of backing the hard left in the region-sent a letter to Secretary of State Colin Powell to complain about U.S. support for Colombia’s military. President George W. Bush answered them with a fresh commitment to the new president to help re-establish the presence of the state across the country. By the time Mr. Uribe left office in 2010, the guerrillas and the paramilitary were nearly eliminated.

Taking a page from the power consolidation carried out by Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, the guerrillas simply changed foxholes. Why get foot rot in the jungle when it’s easy to take over institutions and jail your enemies?

Some saw it coming. A Dec. 1, 2011, letter from two prominent Colombians to the U.S. House Foreign Affairs Committee warned “of the infiltration of [narcoterrorism’s] agents in [the Colombian] judiciary, as well as in [nongovernmental organizations] where under the guise of human rights defenders they support actions to attack democratic institutions.”

The widespread use of bribed or intimidated witnesses in Colombian courts has been acknowledged by legal experts. But there are few consequences for perjurers so the corruption continues.

Whether Mr. Uribe can mount a credible defense remains to be seen. But one thing is certain: Anyone looking for evenhanded jurisprudence won’t find it in today’s Colombia.